Failure seemed to stalk Jacob Davis. Panning for flakes of gold in the rivers of Canada’s western territories yielded mostly dirt and frustration. Patents filed for a steam-powered canal boat and a steam-powered ore crusher failed to generate commercial interest. Shuttered business ventures in wholesale tobacco and pork surely must have shaken his entrepreneurial zeal even further. Finally, when he lost his investment in a brewery in the newly incorporated railroad town of Reno, Nevada, in 1868, Davis returned to his original trade, tailoring.

Jacob Youphes to Jacob Davis1854, the beginning

The story begins in 1854, when 23-year-old Jacob Youphes emigrated from the Baltic coastal city of Riga—now Latvia’s capital, but then part of the Russian Empire. A German-speaking Jew, he arrived in the US hoping to cash in on the burgeoning economy. He anglicized his name to Jacob Davis, and for about two years worked as a tailor in New York and Maine while he learned English. Then he headed west with stays in San Francisco, Victoria and Virginia City, among other towns. More than a decade passed, full of failed endeavors; Davis by then had a family, and he moved them to Reno, where a silver mining bonanza in the Utah Territories was further fueling the economic frenzy there. But once again fortune eluded him. A brewery project in Reno reportedly cost him his life savings. Within a year after arriving there, he opened a simple shop on the main street, where he put his tailoring skills to work making wagon covers, horse blankets, tents and overalls for the railway workers, teamsters and miners crowding the frontier boomtown.1

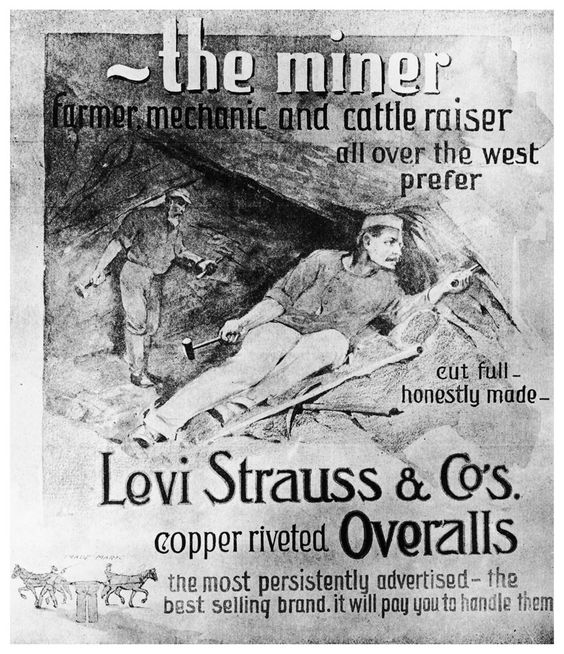

Most workers wore pants and jackets made of either cotton, canvas-like cloth—known as “duck” and dyed off-white or brown—or a lighter, more supple but less sturdy denim cotton weave, sometimes called “blue (indigo-dyed) jean.” Laborers would wear waist overalls with or without suspenders until the pants hung in washed-out tatters. Pockets filled with tools, nails, drill bits and the like often tore, eventually ripping off or hanging down as useless flaps.

Honoring Faster, Better, Cheaper

In December 1870, a year and a half after Davis’ arrival in Reno, a woman entered his shop on Virginia Street to order a pair of pants for her husky woodcutter husband. She agreed to pay $3 in advance, a premium price in those days, for waist overalls that would last. Davis sewed the custom garment with duck, the same 10-ounce cloth used for wagon covers and tents, and added a unique, double-stitched batwing shape on the hip pocket. But as he reviewed the furnished product, he worried that the man’s girth combined with the twisting and stretching required to split railway ties, shape timber for mine shafts, or cut planks and beams would sooner or later ripthe pockets or crotch seam of the pants.

Improvising, the experienced tailor thought of a simple, inexpensive solution: reinforcing the stress points with copper rivets he used for connecting leather straps to horse blankets. “So when the pants were done—the rivets were lying on the table—the thought struck me to fasten the pockets with rivets,” he testified in an 1874 patent infringement case brought by Davis and his future business partner against a competitor. “I have tried experiments with the needle and thread but never before with rivets,” he disclosed in his hand-written deposition.2

Years of practice and exploration— first while apprenticing with master tailors in Riga and later from sewing and repairing various textiles and clothing in his adopted country—crystallized in a single moment of improvisation.

What some might have viewed as a minor incremental improvement turned out to be a transformational innovation. While tailors of his time often used metal buttons and fasteners, apparently no one before Davis had used rivets to supplement stitches in pants. As other workers rushed to order the robust, riveted overalls, fast-rising demand roused Davis’ entrepreneurial nature. In the following 18 months, he reportedly sold about 200 pairs of workpants at the premium price. Demand for the product was as undeniably authentic as the frontier they would come to symbolize.

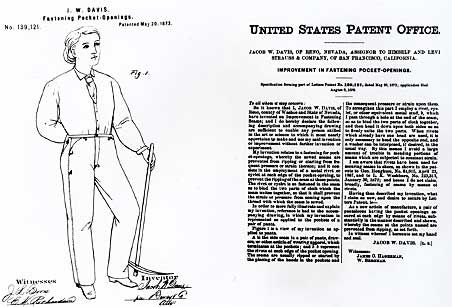

From earlier failures Davis had learned the importance—and sizable expense—of quickly filing a carefully drafted patent to protect an invention. But the poor immigrant lacked the cash and language skill. So to fund the patent, and perhaps to secure a business partner who could supply materials and working capital, the tailor-turned-entrepreneur wrote to his wholesale fabric supplier in San Francisco, Levi Strauss & Co., to propose a partnership. Perhaps a membership in the tailors’ guild of Riga years earlier had cultivated a trust of fellow tradesmen.

He could not keep up with demand for the riveted workpants, Davis reported in his letter, and needed funding for the patent filing. Strauss, also a German-Jewish immigrant who had followed the Gold Rush west, agreed to partner with Davis. Their shared patent, “Improvement in Fastening Pocket-Openings” for riveted trousers, was granted on May 20, 1873.3

The one simple improvement was enough to strongly differentiate overalls produced by Strauss and Davis (which resembled modern Levi’s except that they lacked belt loops 4) from pants made by competitors. Their commercial success reinforced the two men’s partnership and Davis moved his family to San Francisco so he could supervise production. He would eventually sell his share of the patent to Strauss, but only after finally amassing a fortune. City records of the time initially describe the former tailor as “manufacturer” and, by the time of his death, simply as “capitalist.”

It is too easy to dismiss Davis as a simple tailor who got lucky. Both his emigration from Riga, a thriving city in which Jews enjoyed the recent loosening of traditionally anti-semitic restrictions, and his peripatetic wanderings in the New World attested to the venturer’s wanderlust, as did his panning for gold in Canada’s Fraser River. Davis was always patiently exploring and prospecting in search of riches. His diverse patents, and even his stitching, indicated a love of invention and attention to detail. As a result, the product he prototyped in Reno over a century and a half ago continues to literally touch more consumers than perhaps any other invention in history, making him one of the world’s greatest venture craftsmen of all time. (To understand blue jeans’ enduring appeal, read my article on Maslow Applied in the Tools section of venturecraftstudio.com.)

1The discovery of gold in California in 1848, and later the laying of the First Transcontinental Railroad (1863–69) and a manufacturing boom, drew hundreds of thousands of fortune-seekers west.

2 “Forever in blue jeans … and in court,” The National Archives, Pieces of History, 5/20/10

3 Contrary to stories circulated over the years, neither Strauss nor Davis invented blue jeans. Davis’ invention boosted sales of the San Francisco merchant’s overalls simply by addressing a real and widespread need, namely men’s trousers that could withstand rugged working conditions.

4 Harris, M A (2015), “Experience: I Mine for 100-Year-Old Jeans,” The Guardian, September 25, 2015