Antonio Stradivari and his apprentices handcrafted more than 1100 violins, violas, cellos, harps, and guitars in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. The Italian’s prodigious output, said to be greater than that of any luthier of his time, and the financial success documented by his scrupulously maintained records, suggest he was also a disciplined entrepreneur.

The mystery of how Stradivari, whose violins fetch millions of dollars in auctions today, consistently produced stringed instruments of such extraordinary quality remains unsolved more than 300 years after he crafted them in his studio in Cremona, Italy. Experts continue to speculate about relative contributions of the master luthier’s skill at shaping instruments, the chemical composition of his varnish, the age, type, and quality of the woods he used, and his innovations in structural details. MIT researchers recently concluded that variations of as little as 2% in the shape and size of the “f” holes might partially explain the violins’ richer sound.1 2

Two things are certain, though. Firstly, the craftsman was a tinkerer. “Over the course of a 70-year career, Stradivari constantly experimented with the shape and construction of his instruments,” wrote a Financial Times reporter after visiting a 2013 exhibition devoted to the genius at Oxford University. Secondly, he was a masterful designer with a powerful intuition about even the subtlest qualities his customers’ sought in a musical instrument. Violinists today still venerate the distinctive look and feel of a “Strad”, not just its sound.

Like the Italian luthier, modern venture craftsmen think like designers and behave like tinkerers, handcrafting early prototypes well before outside investors sign up. “True craftsmanship, the essence of design, always involves attention to the human dimension and to the perfection of the process that ideally results in the unity of the beautiful with the useful,” wrote Anne J. Banks in What is Design?3 Any innovation can benefit, she writes, “whether the product is a precision instrument, a hand-blown Tiffany vase, a mass produced Eames chair or a surgical procedure.”

For Patrick Robin, award-winning French violin-maker, the secret of Stradivari’s success has been partially explained. The wood, varnish, geometry, and obvious skill of the great master’s apprentices and assistants all contributed. “Only someone who doesn’t understand violin-making could think it was just one thing,” Robin told me during a visit to his studio near Angers, France.

More mysterious, for Robin, are the small adjustments – the experimentation – seen throughout Stradivari’s career. “He was remarkable at Cremona [Italy] in that he was researching constantly,” he said. Was the master trying to achieve the perfect sound? Perhaps, Robin answered. But more likely, Stradivari was continuously exploring “the art of variation”. “The goal is not to make identical instruments but to make varied instruments,” he explained, “because clients are different and have different needs and demands. A violin will sound a particular way depending on the musician. … And the instruments will develop over time, influenced by the quality of the performer.”

Stradivari’s attention to variation presages today’s emphasis on human-centered design. Such solutions are rarely for everyone; they’re designed for some-one. Developers of products as diverse as on-line applications and pre-packaged gourmet meals obsess over the future product’s appeal and ease of use for each customer.

In a two-story stone house on the banks of the Loire river just south of Angers, France, Robin makes some of the most sought-after violins, violas and cellos in Europe today. The only luthier to receive the distinction maître d’art, or master, from the French Ministry of Culture, and winner of several international competitions, Robin’s handcrafted instruments are played by professional performers from Copenhagen to Vienna.

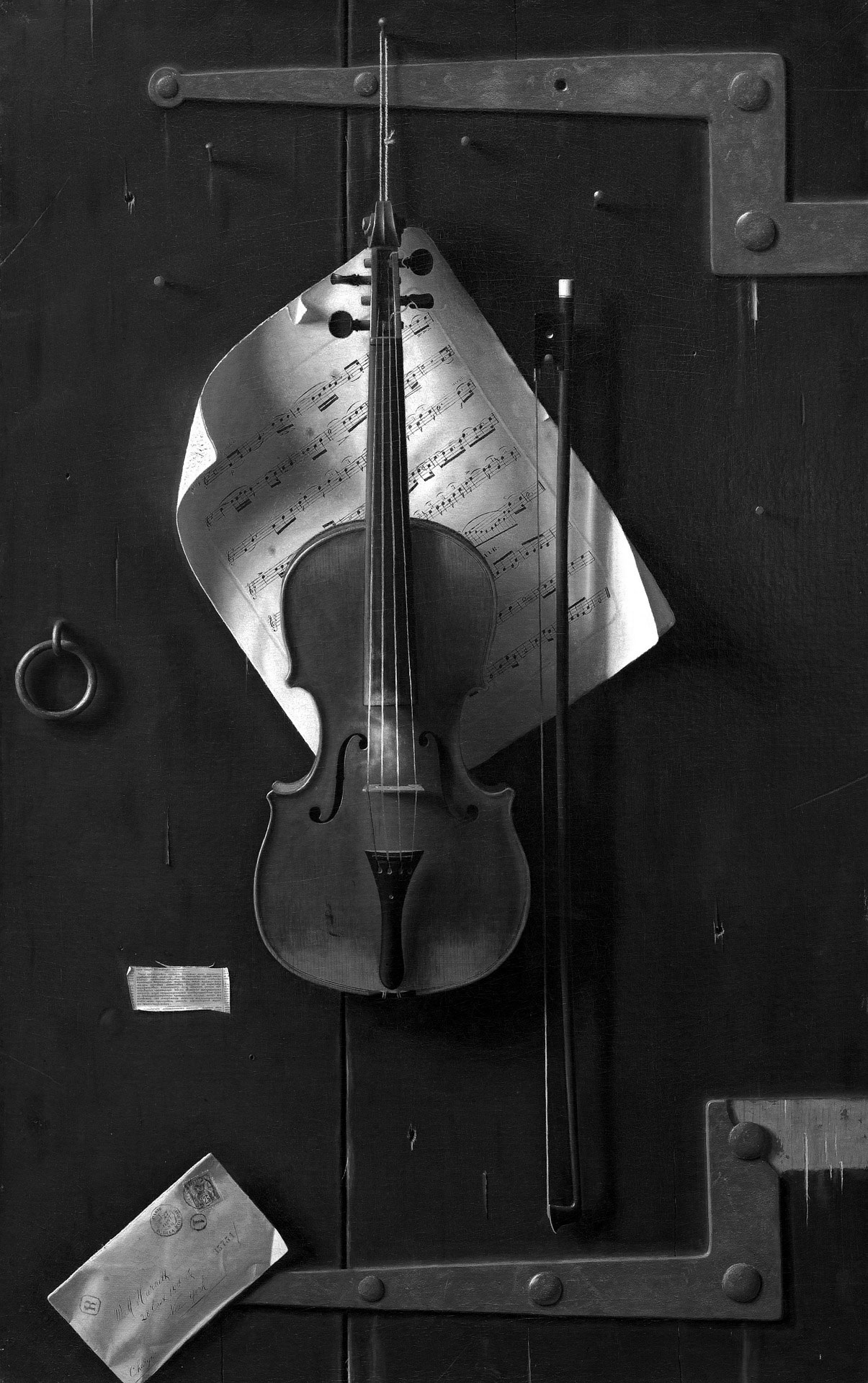

Hanging from the walls in his studio are tools of the trade – handsaws, gouges, planes, mallets, brushes – hardly different from those used by violinmakers since centuries. Plaster molds of instruments made by Italian masters of the 17th and 18th centuries stand in a cabinet in the corner. Even now, many years after completing his apprenticeship, Robin continues to study them closely, remaining in awe before the mystery of their excellence.

“It’s beyond perfectionism,” he says. “There’s a big part which is mastery, and then there is a small part that escapes us, that we can’t and shouldn’t control.”

1 Clark, A (6/21/13), “String Theory”, Financial Times

2 Sawer, P (2/11/15), “Study finds the accidental genius of Stradivarius violins”, The Telegraph

3 Banks, A J (2004), What is design?, Xlibris