In the winter of 1998, Joel Schatz returned to his apartment in San Francisco’s Haight Ashbury neighborhood with a $250,000 investment in his fledgling startup, Datafusion, from the elders of the Oneida Native American tribe. That morning, he had pitched them his supersized vision for solving the world’s problems through software—yet to be designed, coded and sold—that would, he promised, reveal the interconnectedness of all things. Joel, an experienced entrepreneur, predicted his future products would transform how people shared knowledge, discovered innovations, resolved conflicts, improved productivity and protected the environment. Talk about testing the limits of credulity!

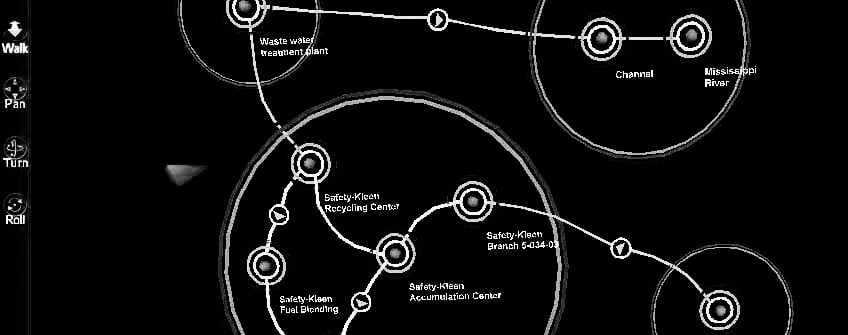

But the Tribal Chief took one look at the beautiful poster-size systems diagrams that Joel’s wife, Diane, had designed to illustrate the vision and said, “This is the digital medicine wheel! We’re in for a quarter of a million.”

A few weeks later, I met Joel and Diane at their office. He looked like a hippie sage, with long beard, hair pulled back in a ponytail and wire-rim glasses. After relating the story of his newly recruited seed investors, he asked: “What do I do with the money?” I stared at him for a moment, unsure of what he meant. “How do I build a company? That’s what I want you to help me with,” he explained.

Early in the stories of successful entrepreneurs, pluck and luck (the formula popularized by Horatio Alger’s dime-store “rags-to-riches” novels of the latter 19th century) sometimes combine to ignite a catalytic spark. For most entrepreneurs, though, combustion of this sort is only one of the initializing conditions for startup incubation. Crafting a sustainable new venture also demands they learn to apply the right skills and tools at the right times. Over the next two years at Datafusion (later renamed Metacode Technologies and sold for $150 million), I learned how to incubate a startup in an uncertain environment with limited resources. Startup failure rate is highest during this delicate phase as new ventures struggle to progress from vision to proof-of-concept.

Initially, having just led the redesign of the new product introduction (NPI) process at a $2 billion-a-year high-tech company in Silicon Valley, I believed we could simply apply a streamlined version of the same NPI blue-print to incubate Datafusion. After all, like Datafusion, the large company had been bringing complex, innovative products to market in a fast-growing, highly competitive industry. I quickly learned, though, that Datafusion’s youth and size fundamentally altered the required approach.

Translating Joel’s grand vision into an initial product and winning beta customers—the early proof points so vital to incubation—immediately presented new challenges. The number of tasks demanding attention often overwhelmed our small team. We struggled to maintain focus. And, in an emerging market, the broad range of potential target customers, a lack of familiarity with their needs and behaviors, and the complexity of solutions we might design far surpassed our capacity to explore and test them all.

Yet cutting corners and making hurried decisions could have had catastrophic consequences for the yet-fragile venture. The pace could not be rushed. Cadence trumps speed at this stage of a business’ life, commonly known as the seed phase. Startup incubation, it seemed, was more exploration than engineering, more art than science. I call it “venture craftsmanship.”

Improv Rules

Within days of my arrival at Datafusion, I was as sold as the elders of the Oneida Tribe on Joel’s product vision: a search engine with a 3-D interface visualizing manmade and natural systems. Users would navigate through interconnected symbols representing the people, places, activities and processes of a virtual factory, city or forest, for example, while seeking information relevant to their queries. We viewed it as the Holy Grail of knowledge management, an emerging category later dominated by the British firm Autonomy, which was launched the same year as Datafusion and acquired by Hewlett-Packard in 2011 for $10.2 billion.

“The thing about creating a business that is completely mystifying is how you actually get an idea—it suddenly pops into your head! Where did it pop from? The fact that you can do that is a kind of miracle.”

Joel was a consummate storyteller. “I’ve always had a silver tongue,” he told me recently. With a simple flipbook presentation (the physical kind) and beautiful, poster-size illustrations of complex systems, he could convert the most skeptical audience. He described products we would build and their future transformational impact on business and government with verve and conviction, adjusting details of the narrative depending on his listeners.

A fundraising meeting with Joel had the energy and good humor of stand-up comedy. (He had successfully used a similar approach when raising seed capital for his previous startup—Global Telesystems—from none other than renowned financier George Soros. But that’s another story—see Chap. 6 of my book Spinning Into Control: Improvising the sustainable startup.)

And Joel applied the same love of improvisation to all other aspects of venture incubation. “The thing about creating a business that is completely mystifying is how you actually get an idea—it suddenly pops into your head! Where did it pop from?” he asked. “The fact that you can do that is a kind of miracle. I don’t take that for granted at all.”

Joel, who studied human behavior at Brandeis University with the renowned psychologist Abraham Maslow, author of the much cited theory about how people strive for self-actualization and personal fulfillment (see details of Maslow’s theory under Tools section of venturecraftstudio.com), regularly set the developers’ heads spinning by moving the boundaries of the project. “I loved challenging our engineers to go outside of their current assignments for ideas about what might drive usage into promising directions. We were always in flux,” he said.

But as a result, I reminded him, our direction often seemed maddeningly haphazard. “We had general plans but had to keep adjusting,” he responded. “We were always very flexible. It was completely necessary to take advantage of opportunities that came out of the blue.”

But didn’t he ever worry about losing control and causing chaos? I asked, recollecting some of the anxious moments I had experienced as the startup’s chief operating officer.

“It’s life,” Joel said. “You just pay attention to daily signals and you make choices.”

More than Joel’s radical product concept, his ability to continuously challenge our engineers and adjust to Datafusion’s evolving situation in real time enabled the venture’s successful outcome. It provided stability and preserved momentum. The acquirer, the price they paid, and the timing of the acquisition were rather random. But that’s ok. Joel kept the good ship afloat until the tide and winds were favorable.